In its present form, the MSP provides only a partial reprieve to farmers, whose fortunes are still exposed to the vagaries of the weather, and the caprices of moneylenders.

Frequent mentions of the minimum support price (MSP) have become a mainstay in political speeches. On July 4, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the highest-ever single-year revision in the MSP of paddy. However, the fine-print of the policy document presents a distorted picture.

When the National Commission on Farmers – headed by MS Swaminathan – gave its recommendations in 2004, it was seen as an inflection point for the agriculture sector. Successive governments have claimed to have raised the MSP to relieve the stress on the agrarian economy, which continues to be plagued by indebtedness, low productivity, and hidden unemployment.

The selective interpretation of the Swaminathan Committee’s recommendations has hindered attempts at resuscitating the farm sector. In its present form, the MSP provides only a partial reprieve to farmers, whose fortunes are still exposed to the vagaries of the weather, and the caprices of moneylenders.

Who sets the MSP?

The Swaminathan Committee’s original recommendation was to fix the MSP at levels “at least 50 per cent more than the weighted average cost of production”. However, the Committee failed to define what constituted the weighted average cost of production.

The government fixes the MSP of 22 mandated agricultural crops based on the recommendation of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP). The list of crops shielded by price fluctuations include 14 kharif crops, six rabi crops, and two commercial crops. The CCAP is also responsible for fixing the fair and remunerative price (FRP) of sugarcane.

The CACP takes into consideration factors such as domestic and international prices, intercrop price parity, the overall demand-supply situation, and also the likely effect of the MSP on inflation.

How is the MSP calculated?

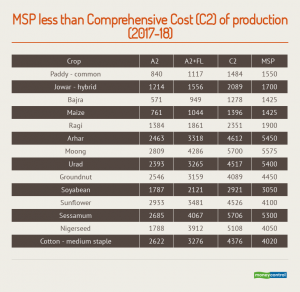

According to the formula prescribed by the Swaminathan Committee, there are three variables that determine production cost – A2, A2+FL, and C2.

A2 includes out-of-pocket expenses borne by farmers, such as term loans for machinery, fertilisers, fuel, irrigation, cost of hired labour and leasing land.

The second metric, A2+FL, takes into account the imputed value of unpaid labour on the part of family members, in addition to the paid-out cost.

The Comprehensive Cost (C2) is more reflective of the actual cost of production since it takes it accounts for rent and interest foregone on owned land and machinery, over and above the A2+FL rate.

The ideal formula according the Committee would be: MSP = C2+ 50% of C2.

Budgetary constraints have held back governments from taking a generous approach while setting the MSP. However, this has not stopped legislators from paying lip service to the primacy of farmers’ interests in government policies.

Is the formula being upheld?

The MSP set by the government for 2017/18 was largely compliant with the Swaminathan Committee’s formula. The MSP was 50 percent more than the cost of production only if the cost was equated to A2. The MSP on paddy was 84.5 percent greater than A2. However, it falls short of the formula in the case of jowar, where the MSP of Rs 1,214 was only 40 percent of A2.

If A2+FL were to be taken as the cost of production, the MSP would meet the Committee’s formula only for three crops, namely bajra, arhar, and urad. Since a large section of the rural population is engaged in agriculture, the cost component accounting for unpaid family labour covered in the A2+FL metric, acquires greater importance. Even then, it is a conservative estimate of how much farmers actually spend in tending to their crops, between sowing and harvesting.

If the MSP were calculated with C2 as the cost of production, not even a single crop would make the cut. The cost of production was not covered by the MSP in the case of half the crops eligible under the scheme.

What about the latest revision?

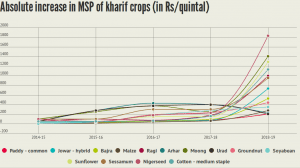

The government announced the MSP for kharif crops for 2018/19 on July 4, 2018. Over the years, previous governments have also increased the quantum of the MSP, but this year’s revised figures were deemed historic as it would be in keeping with the Swaminathan Committee’s recommendation of setting the MSP at 150 percent of the production cost.

The return over cost of all crops is over 50 percent for the first time, redeeming the promise made by the Finance Minister in his Budget speech. The MSP of paddy and jowar are both 50.09 above the production cost, according to data furnished in the Lok Sabha by the Agriculture Minister on July 31. Farmers cultivating pulses will benefit from the move, as the MSP of most varieties have been significantly raised.

In absolute terms, the MSP of kharif crops has increased substantially in 2018/19. The absolute increase in the MSP of paddy is Rs 200/quintal, when compared to Rs 80/quintal, in the year-ago-period. In the case of moong dal, the MSP has increased by as much as Rs 1400/quintal, as opposed to Rs 350/quintal in 2017/18.

But the figures can be misleading. The document lists the MSP of different crops and their cost of production. However, it does not mention which metric was used in computing cost. The return on all 14 crops may be 50 percent above the level of investment of farmers, but the production cost of each was less than the C2 cost for 2017/18. This indicates that the MSP hike would have been less momentous if the government had not taken a lower estimate of production cost.